Harry Belafonte = Mary and the Baby Hungry

| Harry Belafonte | |

|---|---|

Belafonte at the 2011 Tribeca Film Festival Vanity Off-white party | |

| Born | Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. (1927-03-01) March 1, 1927 Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Other names | Harold George Belafonte Jr.

|

| Occupation |

|

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Marguerite Byrd (m. 1948; div. 1957) Julie Robinson (one thousand. 1957; div. 2004) Pamela Frank (g. 2008) |

| Children | 4, including Shari |

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Years agile | 1949–present (music) 1953–present (film) |

Harry Belafonte (born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr.; March i, 1927) is an American singer, songwriter, activist, and player. One of the nigh successful Jamaican-American pop stars, as he popularised the Trinbagonian Caribbean musical style with an international audition in the 1950s. His breakthrough album Calypso (1956) was the first one thousand thousand-selling LP by a single artist.[1]

Belafonte is known for his recording of "The Banana Boat Song", with its signature lyric "Day-O". He has recorded and performed in many genres, including dejection, folk, gospel, show tunes, and American standards. He has likewise starred in several films, including Carmen Jones (1954), Island in the Sun (1957), and Odds Against Tomorrow (1959).

Belafonte considered the actor, singer and activist Paul Robeson a mentor and was a shut confidant of Martin Luther King Jr. in the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s. As he later recalled, "Paul Robeson had been my get-go swell formative influence; you might say he gave me my backbone. Martin Rex was the 2d; he nourished my soul."[ii] Throughout his career, Belafonte has been an advocate for political and humanitarian causes, such as the Anti-Apartheid Move and USA for Africa. Since 1987, he has been a UNICEF Goodwill Administrator.[3] He was a vocal critic of the policies of the George Due west. Bush-league presidential administrations. Belafonte acts every bit the American Ceremonious Liberties Union celebrity ambassador for juvenile justice issues.[4]

Belafonte has won iii Grammy Awards (including a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award), an Emmy Award,[five] and a Tony Award. In 1989, he received the Kennedy Center Honors. He was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1994. In 2014, he received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at the Academy'due south 6th Almanac Governors Awards.[6]

Early life [edit]

Belafonte was built-in Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. [7] at Lying-in Hospital on March ane, 1927, in Harlem, New York, the son of Jamaican-born parents Melvine (née Dearest), a housekeeper, and Harold George Bellanfanti Sr., who worked as a chef.[8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [thirteen] His female parent was the child of a Scottish Jamaican mother and an Afro-Jamaican father, and his father was the kid of a black mother and a Dutch-Jewish father of Sephardic Jewish descent. Harry, Jr. was raised Catholic.[xiv]

From 1932 to 1940, he lived with one of his grandmothers in her native country of Jamaica, where he attended Wolmer's Schools. Upon returning to New York Urban center, he attended George Washington Loftier School[15] afterward which he joined the Navy and served during World War 2.[11] In the 1940s, he was working every bit a janitor's assistant when a tenant gave him, as a gratuity, two tickets to run into the American Negro Theater. He savage in honey with the art class and also met Sidney Poitier. The financially struggling pair regularly purchased a single seat to local plays, trading places in betwixt acts, afterward informing the other about the progression of the play.[16] At the end of the 1940s, he took classes in interim at the Dramatic Workshop of The New School in New York with the influential German director Erwin Piscator alongside Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis, Walter Matthau, Bea Arthur, and Sidney Poitier, while performing with the American Negro Theater. He subsequently received a Tony Honor for his participation in the Broadway revue John Murray Anderson'due south Annual (1954). He also starred in the 1955 Broadway revue 3 for Tonight with Gower Champion.

Music career [edit]

Belafonte started his career in music as a club singer in New York to pay for his acting classes. The first time he appeared in front end of an audience, he was backed past the Charlie Parker ring, which included Charlie Parker himself, Max Roach and Miles Davis, amidst others. At first, he was a pop vocalizer, launching his recording career on the Roost label in 1949, merely later he developed a cracking interest in folk music, learning material through the Library of Congress' American folk songs archives. With guitarist and friend Millard Thomas, Belafonte soon fabricated his debut at the legendary jazz club The Village Vanguard. In 1953, he signed a contract with RCA Victor, recording regularly for the characterization until 1974.

Belafonte too performed during the Rat Pack era in Las Vegas. He and associated acts such equally Liberace, Ray Vasquez, and Sammy Davis Jr. were featured at the Sands Hotel and Casino and the Dunes Hotel.

Calypso [edit]

Belafonte's outset widely released single, which went on to become his "signature" audience participation vocal in virtually all his live performances, was "Matilda", recorded April 27, 1953. His breakthrough anthology Calypso (1956) became the first LP in the globe "to sell over 1 million copies inside a year", Belafonte confirmed on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's The Link program on August seven, 2012. He added that it was besides the first one thousand thousand-selling album ever in England. The album is number four on Billboard 's "Top 100 Album" list for having spent 31 weeks at number one, 58 weeks in the height 10, and 99 weeks on the U.Southward. charts. The album introduced American audiences to calypso music (which had originated in Trinidad and Tobago in the early 20th century), and Belafonte was dubbed the "King of Calypso", a title he wore with reservations since he had no claims to any Calypso Monarch titles.

I of the songs included in the album is the now famous "Assistant Gunkhole Song" (listed as "Mean solar day-O" on the Calypso LP), which reached number v on the pop charts, and featured its signature lyric "Twenty-four hour period-O".[17]

Many of the compositions recorded for Calypso, including "Banana Boat Song" and "Jamaica Bye", gave songwriting credit to Irving Burgie.

Middle career [edit]

With Julie Andrews on the NBC special An Evening with Julie Andrews and Harry Belafonte (1969)

While primarily known for calypso, Belafonte has recorded in many unlike genres, including dejection, folk, gospel, show tunes, and American standards. His second-most popular striking, which came immediately after "The Banana Gunkhole Song", was the comedic tune "Mama Expect at Bubu", too known every bit "Mama Look a Boo-Boo" (originally recorded by Lord Tune in 1955[18]), in which he sings humorously about misbehaving and disrespectful children. Information technology reached number eleven on the pop chart.

In 1959, Belafonte starred in Tonight With Belafonte, a nationally televised special that featured Odetta, who sang "Water Boy" and who performed a duet with Belafonte of "There'south a Hole in My Bucket" that hitting the national charts in 1961.[xix] Belafonte was the first Jamaican American to win an Emmy, for Revlon Revue: This night with Belafonte (1959).[five] Two live albums, both recorded at Carnegie Hall in 1959 and 1960, enjoyed critical and commercial success. From his 1959 album, "Hava Nagila" became part of his regular routine and one of his signature songs.[20] He was i of many entertainers recruited by Frank Sinatra to perform at the inaugural gala of President John F. Kennedy in 1961. Afterwards that year, RCA Victor released some other calypso album, Jump Up Calypso, which went on to become some other meg seller. During the 1960s he introduced several artists to American audiences, well-nigh notably South African vocalizer Miriam Makeba and Greek vocalizer Nana Mouskouri. His anthology Midnight Special (1962) included a young harmonica player named Bob Dylan.

Every bit The Beatles and other stars from Britain began to dominate the U.S. pop charts, Belafonte'south commercial success macerated; 1964's Belafonte at The Greek Theatre was his last anthology to appear in Billboard 's Top 40. His last hit single, "A Foreign Vocal", was released in 1967 and peaked at number v on the adult contemporary music charts. Belafonte has received Grammy Awards for the albums Swing Dat Hammer (1960) and An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba (1965). The latter album dealt with the political plight of black South Africans nether apartheid. He earned six Gilt Records.[21]

During the 1960s, Belafonte appeared on TV specials alongside such artists as Julie Andrews, Petula Clark, Lena Horne, and Nana Mouskouri. In 1967, Belafonte was the first non-classical artist to perform at the prestigious Saratoga Performing Arts Center (SPAC) in Upstate New York, soon to be followed by concerts there by The Doors, The 5th Dimension, The Who, and Janis Joplin.

From Feb 5 to 9, 1968, Belafonte invitee hosted The Tonight Show substituting for Johnny Carson. Among his interview guests were Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy.[22]

Later recordings and other activities [edit]

Belafonte's fifth and final calypso album, Calypso Funfair was issued by RCA in 1971. Belafonte's recording activity slowed considerably afterwards releasing his last album for RCA in 1974. From the mid-1970s to early 1980s, Belafonte spent the greater office of his time on tour, which included concerts in Nippon, Europe, and Cuba. In 1977, Columbia Records released the album Turn the World Around, with a potent focus on world music. Columbia never issued the album in the U.s.a.. He after was a guest star on a memorable episode of The Muppet Evidence in 1978, in which he performed his signature song "Mean solar day-O". However, the episode is best known for Belafonte's rendition of the spiritual song "Turn the World Around", from the album of the same name, which he performed with specially fabricated Muppets that resembled African tribal masks. It became one of the series' nearly famous performances and was reportedly Jim Henson's favorite episode. Afterward Henson's death in May 1990, Belafonte was asked to perform the song at Henson's memorial service. "Turn the World Around" was also included in the 2005 official hymnal supplement of the Unitarian Universalist Association, Singing the Journey.[23]

Belafonte's involvement in USA for Africa during the mid-1980s resulted in renewed interest in his music, culminating in a record deal with EMI. He later on released his first album of original fabric in over a decade, Paradise in Gazankulu, in 1988. The album contains x protest songs against the Due south African former Apartheid policy and is his terminal studio anthology. In the same yr Belafonte, as UNICEF Goodwill Administrator, attended a symposium in Harare, Zimbabwe, to focus attention on child survival and development in Southern African countries. As part of the symposium, he performed a concert for UNICEF. A Kodak video crew filmed the concert, which was released as a sixty-infinitesimal concert video titled "Global Carnival". It features many of the songs from the album Paradise in Gazankulu and some of his archetype hits. Also in 1988, Tim Burton used "The Banana Boat Vocal" and "Jump in the Line" in his moving picture Beetlejuice.[ commendation needed ]

Following a lengthy recording hiatus, An Evening with Harry Belafonte and Friends, a soundtrack and video of a televised concert, were released in 1997 by Isle Records. The Long Road to Freedom: An Anthology of Black Music, a huge multi-artist project recorded past RCA during the 1960s and 1970s, was finally released by the label in 2001. Belafonte went on the Today Show to promote the album on September eleven, 2001, and was interviewed by Katie Couric just minutes before the first plane hit the Globe Merchandise Center.[24] The album was nominated for the 2002 Grammy Awards for Best Boxed Recording Packet, for All-time Album Notes, and for Best Historical Album.[ citation needed ]

Belafonte received the Kennedy Heart Honors in 1989. He was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1994 and he won a Grammy Lifetime Accomplishment Laurels in 2000. He performed sold-out concerts globally through the 1950s to the 2000s. Attributable to disease, he was forced to abolish a reunion tour with Nana Mouskouri planned for the spring and summertime of 2003 following a tour in Europe. His concluding concert was a benefit concert for the Atlanta Opera on October 25, 2003. In a 2007 interview, he stated that he had since retired from performing.[25]

On Jan 29, 2013, Belafonte was the Keynote Speaker and 2013 Honoree for the MLK Commemoration Series at the Rhode Isle School of Design. Belafonte used his career and experiences with Dr. King to speak on the role of artists equally activists.[26]

Belafonte was inducted as an honorary member of Phi Beta Sigma fraternity on Jan xi, 2014.[27]

In March 2014, Belafonte was awarded an honorary doctorate from Berklee Higher of Music in Boston.[28]

In 2017, Belafonte released When Colors Come Together, an anthology of some of Belafonte's earlier recordings produced past his son David who wrote lyrics for an updated version of "Isle In The Sunday", arranged by longtime Belafonte musical managing director Richard Cummings, and featuring Harry Belafonte's grandchildren Sarafina and Amadeus and a children's choir.

Film career [edit]

Belafonte at the 2011 Berlin Film Festival

Belafonte has starred in several films. His first film part was in Bright Route (1953), in which he appeared alongside Dorothy Dandridge. The two subsequently starred in Otto Preminger'due south hitting musical Carmen Jones (1954). Ironically, Belafonte's singing in the film was dubbed past an opera singer, as Belafonte's own singing vox was seen as unsuitable for the role. Using his star clout, Belafonte was after able to realize several and so-controversial film roles. In 1957's Isle in the Sun, at that place are hints of an affair betwixt Belafonte's graphic symbol and the character played by Joan Fontaine. The flick as well starred James Stonemason, Dandridge, Joan Collins, Michael Rennie, and John Justin. In 1959, he starred in and produced, through his visitor HarBel Productions, Robert Wise's Odds Against Tomorrow, in which he plays a bank robber uncomfortably teamed with a racist partner (Robert Ryan). He besides co-starred with Inger Stevens in The World, the Mankind and the Devil. Belafonte was offered the role of Porgy in Preminger'south Porgy and Bess, where he would have one time once more starred contrary Dandridge, merely he refused the role considering he objected to its racial stereotyping.

Dissatisfied with most of the film roles offered to him, he full-bodied on music during the 1960s. In the early on 1970s, Belafonte appeared in more films, amidst which are 2 with Poitier: Buck and the Preacher (1972) and Uptown Sat Nighttime (1974). In 1984, Belafonte produced and scored the musical film Beat Street, dealing with the ascension of hip-hop culture. Together with Arthur Baker, he produced the gilt-certified soundtrack of the same name. Belafonte side by side starred in a major film once more in the mid-1990s, appearing with John Travolta in the race-reverse drama White Man'southward Burden (1995); and in Robert Altman's jazz historic period drama Kansas Urban center (1996), the latter of which garnered him the New York Film Critics Circumvolve Award for Best Supporting Actor. He besides starred every bit an Associate Justice of the Supreme Courtroom of the The states in the TV drama Swing Vote (1999). In 2006, Belafonte appeared in Bobby, Emilio Estevez'due south ensemble drama about the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy; he played Nelson, a friend of an employee of the Ambassador Hotel (Anthony Hopkins). He appears in Spike Lee's BlacKkKlansman (2018) as an elderly civil rights pioneer.

Personal life [edit]

2nd wife Julie Belafonte

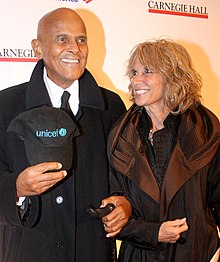

Belafonte with tertiary wife Pamela in April 2011

Belafonte and Marguerite Byrd were married from 1948 to 1957. They have ii daughters: Adrienne and Shari Belafonte. They separated when Byrd was pregnant with Shari.[29] Adrienne and her daughter Rachel Blueish founded the Anir Foundation / Experience, focused on humanitarian work in southern Africa.[30] Shari is a photographer, model, vocaliser, and extra and is married to thespian Sam Behrens.

In 1953, Belafonte was financially able to move from Washington Heights, Manhattan "into a white neighborhood in Elmhurst, Queens."[31]

Belafonte had an affair with actress Joan Collins during the filming of Island in the Sun.[32]

On March 8, 1957, Belafonte married his second wife Julie Robinson, a old dancer with the Katherine Dunham Company who was of Jewish descent.[33] They had ii children, David and Gina. David, the only son of Harry Belafonte, is a former model and actor and is an Emmy-winning and Grammy nominated music producer and the executive director of the family-held company Belafonte Enterprises Inc. As a music producer, David has been involved in most of Belafonte's albums and tours and productions. He is married to model and vocalizer Malena Belafonte who toured with Belafonte. Gina Belafonte is a TV and picture actress and worked with her male parent as omnibus and producer on more than six films.

Subsequently 47 years of wedlock,[34] Belafonte and Robinson divorced. In Apr 2008, Belafonte married lensman Pamela Frank.[35]

Belafonte has 5 grandchildren, Rachel and Brian through his children with Marguerite Byrd, and Maria, Sarafina, and Amadeus through his children with Julie Robinson. In October 1998, Belafonte contributed a letter to Liv Ullmann's book Letter to My Grandchild.[36]

Political and humanitarian activism [edit]

Belafonte is said to accept married politics and popular culture.[29] Belafonte'southward political beliefs were greatly inspired by the singer, actor and civil rights activist Paul Robeson, who mentored him. Robeson opposed not only racial prejudice in the United States but also western colonialism in Africa. He refused to perform in the American Southward from 1954 until 1961. In 1960, he appeared in a entrada commercial for Democratic Presidential candidate John F. Kennedy.[37] Kennedy later named Belafonte cultural advisor to the Peace Corps.

Belafonte gave the keynote address at the ACLU of Northern California'due south annual Beak of Rights Twenty-four hours Celebration In December 2007 and was awarded the Main Justice Earl Warren Civil Liberties Award. The 2011 Sundance Film Festival featured the documentary film Sing Your Song, a biographical pic focusing on Belafonte'due south contribution to and his leadership in the civil rights movement in America and his endeavors to promote social justice globally.[38] In 2011, Belafonte'southward memoir My Song was published by Knopf Books.

Involvement in Civil Rights Movement [edit]

Belafonte supported the Ceremonious Rights Motion in the 1950s and 1960s and was one of Martin Luther Male monarch Jr.'due south confidants. He provided for King's family since Rex made simply $8,000 a yr equally a preacher. Like many other ceremonious rights activists, Belafonte was blacklisted during the McCarthy era. During the 1963 Birmingham Entrada, he bailed King out of Birmingham City Jail and raised $50,000[39] to release other civil rights protesters. He financed the 1961 Freedom Rides, supported voter registration drives, and helped to organize the 1963 March on Washington.

During the "Mississippi Freedom Summer" of 1964, Belafonte bankrolled the Educatee Irenic Coordinating Committee, flying to Mississippi that Baronial with Sidney Poitier and $60,000 in cash and entertaining crowds in Greenwood. In 1968, Belafonte appeared on a Petula Clark primetime television special on NBC. In the heart of a duet of On the Path of Glory, Clark smiled and briefly touched Belafonte's arm,[40] which prompted complaints from Doyle Lott, the advertising managing director of the bear witness's sponsor, Plymouth Motors.[41] Lott wanted to retape the segment,[42] but Clark, who had buying of the special, told NBC that the performance would be shown intact or she would not allow it to be aired at all. Newspapers reported the controversy,[43] [44] Lott was relieved of his responsibilities,[45] and when the special aired, information technology attracted high ratings.

Belafonte appeared on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hr on September 29, 1968, performing a controversial "Mardi Gras" number intercut with footage from the 1968 Autonomous National Convention riots. CBS censors deleted the segment. The full unedited content were broadcast in 1993 as part of a complete Smothers Brothers Hr syndication package.

Humanitarian activism [edit]

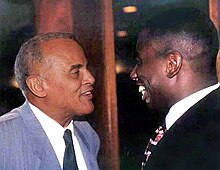

Belafonte (left) with activist and opera star Stacey Robinson in 1988.

In 1985, he helped organize the Grammy Award-winning vocal "We Are the Earth", a multi-creative person effort to enhance funds for Africa. He performed in the Alive Aid concert that same year. In 1987, he received an appointment to UNICEF as a goodwill ambassador. Following his appointment, Belafonte traveled to Dakar, Senegal, where he served as chairman of the International Symposium of Artists and Intellectuals for African Children. He as well helped to enhance funds—alongside more than xx other artists—in the largest concert ever held in sub-Saharan Africa. In 1994, he went on a mission to Rwanda and launched a media campaign to raise awareness of the needs of Rwandan children.

In 2001, he went to South Africa to support the campaign against HIV/AIDS. In 2002, Africare awarded him the Bishop John T. Walker Distinguished Humanitarian Service Honor for his efforts to aid Africa. In 2004, Belafonte went to Republic of kenya to stress the importance of educating children in the region.

Belafonte has been involved in prostate cancer advocacy since 1996, when he was diagnosed and successfully treated for the illness.[46] On June 27, 2006, Belafonte was the recipient of the BET Humanitarian Award at the 2006 BET Awards. He was named one of nine 2006 Impact Award recipients by AARP The Magazine.[47] On October 19, 2007, Belafonte represented UNICEF on Norwegian television set to support the annual telethon (TV Aksjonen) in support of that charity and helped heighten a world record of $10 per inhabitant of Kingdom of norway. Belafonte was also an ambassador for the Bahama islands.[ commendation needed ] He is on the board of directors of the Advancement Project.[48] He also serves on the Advisory Quango of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation.

Political activism [edit]

Belafonte has been a longtime critic of U.S. strange policy. He began making controversial political statements on this subject in the early 1980s. He has at diverse times fabricated statements opposing the U.S. embargo on Cuba; praising Soviet peace initiatives; attacking the U.Due south. invasion of Grenada; praising the Abraham Lincoln Brigade; honoring Ethel and Julius Rosenberg and praising Fidel Castro.[ commendation needed ] Belafonte is additionally known for his visit to Cuba which helped ensure hip-hop's place in Cuban society. According to Geoffrey Baker's article "Hip hop, Revolucion! Nationalizing Rap in Cuba", in 1999, Belafonte met with representatives of the rap community immediately earlier coming together with Fidel Castro. This coming together resulted in Castro's personal approval of, and hence the government's involvement in, the incorporation of rap into his state's culture.[49] In a 2003 interview, Belafonte reflected upon this meeting's influence:

"When I went back to Havana a couple years later, the people in the hip-hop community came to see me and we hung out for a flake. They thanked me profusely and I said, 'Why?' and they said, 'Because your picayune conversation with Fidel and the Minister of Civilisation on hip-hop led to there beingness a special partition inside the ministry and nosotros've got our own studio'."[50]

Belafonte was agile in the Anti-Apartheid Movement. He was the Primary of Ceremonies at a reception honoring African National Congress President Oliver Tambo at Roosevelt Firm, Hunter College, in New York City. The reception was held past the American Commission on Africa (ACOA) and The Africa Fund.[51] He is a current board member of the TransAfrica Forum and the Institute for Policy Studies.[52]

Opposition to the George W. Bush administration [edit]

Belafonte achieved widespread attention for his political views in 2002 when he began making a series of comments about President George Due west. Bush, his assistants and the Iraq War. During an interview with Ted Leitner for San Diego'due south 760 KFMB, on October 10, 2002, Belafonte referred to a quote made by Malcolm 10.[53] Belafonte said:

There is an old saying, in the days of slavery. There were those slaves who lived on the plantation, and there were those slaves who lived in the house. You got the privilege of living in the house if you served the master, do exactly the manner the master intended to accept y'all serve him. That gave you privilege. Colin Powell is committed to come into the house of the main, as long as he would serve the master, co-ordinate to the primary's purpose. And when Colin Powell dares to suggest something other than what the master wants to hear, he will exist turned back out to pasture. And you don't hear much from those who live in the pasture.

Belafonte used the quote to characterize former United States Secretaries of State Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice, Powell and Rice both responded, with Powell calling the remarks "unfortunate"[54] and Rice maxim: "I don't need Harry Belafonte to tell me what information technology ways to be black."[55]

The comment was brought up over again in an interview with Amy Goodman for Democracy Now! in 2006.[56] In Jan 2006, Belafonte led a delegation of activists including role player Danny Glover and activist/professor Cornel West to meet with President of Venezuela Hugo Chávez. In 2005, Chávez, an outspoken Bush critic, initiated a program to provide cheaper heating oil for poor people in several areas of the United states. Belafonte supported this initiative.[57] He was quoted as maxim, during the meeting with Chávez, "No matter what the greatest tyrant in the earth, the greatest terrorist in the world, George W. Bush says, we're here to tell you: Not hundreds, not thousands, but millions of the American people support your revolution."[58] Belafonte and Glover met once more with Chávez in 2006.[59] The comment ignited a great deal of controversy. Hillary Clinton refused to acknowledge Belafonte'due south presence at an awards anniversary that featured both of them.[60] AARP, which had merely named him one of its 10 Impact Honour honorees 2006, released this statement following the remarks: "AARP does not condone the manner and tone which he has chosen and finds his comments completely unacceptable."[61] During a Martin Luther King Jr. Solar day speech communication at Duke University in 2006, Belafonte compared the American government to the hijackers of the September xi attacks, saying: "What is the deviation betwixt that terrorist and other terrorists?" [62] In response to criticism about his remarks Belafonte asked, "What do you call Bush when the state of war he put us in to date has killed well-nigh equally many Americans as died on 9/11 and the number of Americans wounded in war is almost triple? ... By most definitions Bush-league can be considered a terrorist." When he was asked about his expectation of criticism for his remarks on the state of war in Iraq, Belafonte responded: "Bring it on. Dissent is central to whatsoever commonwealth."[63]

In some other interview, Belafonte remarked that while his comments may have been "jerky", nevertheless he felt the Bush administration suffered from "arrogance wedded to ignorance" and its policies around the earth were "morally bankrupt".[64] In January 2006, in a spoken language to the annual meeting of the Arts Presenters Members Conference, Belafonte referred to "the new Gestapo of Homeland Security" saying, "Y'all can be arrested and have no right to counsel!"[65] During the Martin Luther King Jr. Solar day spoken communication at Duke University in January 2006, Belafonte said that if he could choose his epitaph it would be, "Harry Belafonte, Patriot."[66]

In 2004, he was awarded the Domestic Homo Rights Accolade in San Francisco by Global Exchange.

Obama administration [edit]

In the 1950s, Belafonte was a supporter of the African American Students Foundation, which in 1959 gave a grant to Barack Obama Sr., the late father of 40-quaternary U.s.a. president Barack Obama 2, to study at the University of Hawaii.[67]

In 2011, he commented on the Obama administration and the role of popular opinion in shaping its policies. "I think [Obama] plays the game that he plays because he sees no threat from evidencing concerns for the poor."[68]

On Dec ix, 2012, in an interview with Al Sharpton on MSNBC, Belafonte expressed dismay that many political leaders in the United states keep to oppose the policies of President Obama even afterwards his re-election: "The only matter left for Barack Obama to do is to work like a tertiary-globe dictator and but put all of these guys in jail. Yous're violating the American desire."[69]

On February 1, 2013, Belafonte received the NAACP'southward Spingarn Medal, and in the televised ceremony, he counted Constance L. Rice among those previous recipients of the award whom he regarded highly for speaking upward "to remedy the ills of the nation".[70]

NYC Pride [edit]

In 2013, he was named a Grand Align of the New York Metropolis Pride Parade, alongside Edie Windsor and Earl Fowlkes.[71]

2016 presidential election [edit]

In 2016, Belafonte endorsed Bernie Sanders for the Democratic Primary, saying: "I call up he represents opportunity, I call up he represents a moral imperative, I think he represents a certain kind of truth that's non often evidenced in the course of politics".[72]

Belafonte was an honorary co-chair of the Women's March on Washington, which took place on January 21, 2017, the day afterward the Inauguration of Donald Trump as president.[73]

2020 presidential election [edit]

Harry Belafonte is a Fellow at The Sanders Institute, which has a mission to "revitalize democracy by actively engaging individuals, organizations and the media in the pursuit of progressive solutions to economic, environmental, racial and social justice issues."[74]

Business career [edit]

Harry Belafonte likes and has often visited the Caribbean island of Bonaire.[75] He and Maurice Neme of Oranjestad, Aruba formed a joint venture to create a luxurious private community on Bonaire. On 3 June 1966, the construction of the neighbourhood started which was named Belnem afterward Belafonte and Neme.[76] The neighbourhood is managed by the Bel-Nem Caribbean area Evolution Corporation. Belafonte and Neme served as its first directors.[77] In 2017, Belnem was home to 717 people.[78]

Discography [edit]

Belafonte has released 30 studio albums and 8 live albums, and has achieved critical and commercial success.

Filmography [edit]

- Brilliant Road (1953)

- Carmen Jones (1954)

- Island in the Sun (1957)

- The Heart of Evidence Business concern (1957) (short subject field)

- The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959)

- Odds Confronting Tomorrow (1959)

- Rex: A Filmed Record... Montgomery to Memphis (1970) (documentary) (narrator)

- The Angel Levine (1970)

- Cadet and the Preacher (1972)

- Uptown Sat Night (1974)

- Fundi: The Story of Ella Baker (1981) (documentary)

- A veces miro mi vida (1982)

- Drei Lieder (1983) (short field of study)

- Sag nein (1983) (documentary)

- Der Schönste Traum (1984) (documentary)

- We Shall Overcome (1989) (documentary) (narrator)

- The Player (1992) (Cameo)

- Ready to Wear (1994) (Cameo)

- Hank Aaron: Chasing the Dream (1995)

- White Homo's Brunt (1995)

- Jazz '34 (1996)

- Kansas City (1996)

- Scandalize My Name: Stories from the Blacklist (1998) (documentary)

- Swing Vote (1999) (telly-motion picture)

- Fidel (2001) (documentary)

- XXI Century (2003) (documentary)

- Conakry Kas (2003) (documentary)

- Ladders (2004) (documentary) (narrator)

- Mo & Me (2006) (documentary)

- Bobby (2006)

- Motherland (2009) (documentary)

- Sing Your Song (2011) (documentary)

- Hava Nagila: The Movie (2013) (documentary)

- BlacKkKlansman (2018)

- The Sit-in: Harry Belafonte hosts the Tonight Prove (2020) (documentary)

Tv piece of work [edit]

Actualization (2nd from left) on British television discussion programme After Dark in 1988

- Sugar Hill Times (1949–1950)

- The Ed Sullivan Show (1953-1964, x times)

- The Steve Allen Testify (1958)[79]

- Tonight With Belafonte (1959)

- 1963 Round Table (1963)

- Petula (1968)

- The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (1968)

- The Tonight Evidence (1968)

- A World in Music (1969)

- Harry & Lena, For The Dear Of Life (1969)

- A World in Dearest (1970)

- The Flip Wilson Testify (1973)

- Free to Be ... You lot and Me (1974)

- The Muppet Prove (1978)

- Grambling'southward White Tiger (1981)

- Don't Finish The Carnival (1985)

- After Night (1989) (extended appearance on political discussion program, more hither)

- An Evening with Harry Belafonte and Friends (1997)

- Swing Vote (1999)

- PB&J Otter "The Water ice Moose" (1999)

- Tanner on Tanner (2004)

- That's What I'm Talking Nigh (2006) (miniseries)

- When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts (2006) (miniseries)

- Speakeasy, interviewing Carlos Santana (2015)[lxxx]

Concert videos [edit]

- En Gränslös Kväll På Operan (1966)

- Don't Stop The Carnival (1985)

- Global Carnival (1988)

- An Evening with Harry Belafonte and Friends (1997)

Phase piece of work [edit]

- John Murray Anderson'south Almanac (1953)

- iii for Tonight (1955)

- Moonbirds (1959) (producer)

- Belafonte at the Palace (1959)

- Asinamali! (1987) (producer)

Legacy [edit]

Belafonte celebrated his 93rd birthday on March i, 2020, at Harlem's Apollo Theater in a tribute event that concluded "with a thunderous audience singalong" with rapper Doug East. Fresh to 1956's "Assistant Gunkhole Song". Presently after, the New York Public Library's Schomburg Center for Research in Black Civilization appear it had acquired Belafonte's vast personal archive - a lifetime's worth of "photographs, recordings, films, messages, artwork, clipping albums," etc.[81]

See also [edit]

- Listing of peace activists

References [edit]

- ^ "Harry Belafonte - Calypso". AllMusic (All Media Network). Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ Belafonte, Harry; Shnayerson, Michael (2011). My Song: A Memoir. New York: Knopf. p. 297. ISBN978-0-307-27226-3.

- ^ "Unicef Names Belafonte Expert-Volition Ambassador". The New York Times. March 9, 1987 – via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ "ACLU Ambassadors - Harry Belafonte". aclu.olrg (American Civil Liberties Union). Retrieved Jan 5, 2015.

- ^ a b "Awards search for Harry Belafonte". Emmys. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ Sinha-Roy, Piya (Baronial 28, 2014). "Belafonte, Miyazaki to receive Academy's Governors Awards". Reuters . Retrieved Baronial 28, 2014.

- ^ "Life in Harlem". Sing Your Song. S2BN Belafonte Productions. Archived from the original on October 14, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ Genia Fogelson (1996). Harry Belafonte. Holloway Firm Publishing. p. 13. ISBN0-87067-772-one.

- ^ Hardy, Phil; Dave Laing (1990). The Faber Companion to Twentieth Century Music. Faber. p. 54. ISBN0-571-16848-5.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte Biography (1927-)". Film Reference. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ a b The African American Registry Harry Belafonte, an entertainer of truth Archived July xvi, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Calypso Artists: Harry Belafonte". February viii, 2009. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ Fogelson, Genia (September 1, 1996). Harry Belafonte. ISBN978-0-87067-772-4.

- ^ Keillor, Garrison (October 21, 2011). "The Radical Entertainment of Harry Belafonte (Published 2011)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ Arenson, Karen W. "Commencements; Belafonte Lauds Diversity Of Baruch Higher Class", The New York Times, June ii, 2000. Retrieved April 16, 2008. "(He said that he had not gotten past the first year at George Washington High Schoolhouse, and that the only college degrees he had were honorary ones.)"

- ^ Belafonte, Harry (October 12, 2011). "Harry Belafonte: Out Of Struggle, A Beautiful Voice". NPR. Retrieved November five, 2013.

- ^ Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 18 – Blowin' in the Wind: Pop discovers folk music. [Part 1] : UNT Digital Library". Pop Chronicles . Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Lord Melody / Caribbean All Stars Band - The Bo-Bo-Man / Saxophone Limbo". Discogs . Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ "Odetta". WordPress. Retrieved December x, 2013.

- ^ Grossman, Roberta (2011). "Video – What does Hava Nagila mean?". YouTube. Archived from the original on Dec 11, 2021.

- ^ "Searchable Database - Search: Belafonte Makeba". RIAA. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ "MLK Appears on "Tonight" Show with Harry Belafonte". The Martin Luther Rex Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Alter. February 2, 1968. Retrieved November five, 2013.

- ^ "Vocal Data". UUA. April nine, 2012. Archived from the original on October 12, 2010. Retrieved Nov 5, 2013.

- ^ "NBC Sept. 11, 2001 eight:31 am - 9:12 am". Net Archive. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ "kostenloses PR und Pressemitteilungen". Pr-inside.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved November five, 2013.

- ^ "2013 MLK Series Keynote Address – Harry Belafonte 'Artist as Activist'". RISD. January 29, 2013.

- ^ Brown, DeNeen L. (Jan 12, 2014). "Harry Belafonte challenges Phi Beta Sigma to join movement to terminate oppression of women". The Washington Post . Retrieved Jan fourteen, 2014.

- ^ "ACLU Administrator Project". American Civil Liberties Union . Retrieved July xvi, 2019.

- ^ a b Harry Belafonte He Married Politics and Pop Culture People mag Feb 21, 2022 Page 39 By magazine staff & Shari Belafonte

- ^ "Anir Experience". Anir Foundation. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ Gates Jr., Henry Louis. "Belafonte's Balancing Act", The New Yorker, August 26, 1996. Accessed March 19, 2019. "In 1953, enjoying his commencement real taste of affluence, Belafonte moved from Washington Heights into a white neighborhood in Elmhurst, Queens."

- ^ Colina, Erin (October fourteen, 2013). "Joan Collins Shares Steamy Details of Affairs with Harry Belafonte and Warren Beatty". Parade.

- ^ Bloom, Nate (November 17, 2011). "Jewish Stars 11/18". Cleveland Jewish News.

His second wife, dancer Julie Robinson, to whom he was married from 1958-2004, is Jewish. They had a daughter Gina, l, and a son David, 54

- ^ Mottran, James (May 27, 2012). "Interview: Harry Belafonte, vocalist". The Scottsman.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte Fast Facts". CNN. July 7, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ Ullmann, Liv (October 1998). Letter to My Grandchild. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN0-87113-728-three.

- ^ "Commercials - 1960 - Harry Belafonte". The Living Room Candidate. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ Macdonald, Moira. "Movies | 'Sing Your Song' recounts Harry Belafonte's life". The Seattle Times . Retrieved Nov v, 2013.

- ^ King, Jr., Martin Luther (January 2001). The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr . p. 185. ISBN978-0-446-67650-2.

- ^ Harry Belafonte with Petula Clark – On The Path Of Celebrity on YouTube

- ^ "Tempest in TV Tube Is Sparked by Touch". Spokane Daily Chronicle. AP. March 5, 1968. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ "Bellafonte Hollers; Chrysler Says Everything's All Right". The Dispatch. Lexington, North Carolina. UPI. March vii, 1968. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ "Chrysler Rejects Charges Of Discrimination In Testify". The Morning Tape. Meriden–Wallingford, Connecticut. AP. March vii, 1968. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ "Belafonte says apologies can't modify centre, color". The Afro American. March xvi, 1968. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ "Belafonte Ire Brings Penalisation: Chrysler Official Apologizes To Star". Toledo Blade. AP. March 11, 1968. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte and prostate cancer". Phoenix5.org. Apr 21, 1997. Retrieved November five, 2013.

- ^ "Feel Great. Save Money. Have Fun". AARP The Magazine. May 26, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Advancement Project". Advocacy Project. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ Baker, Geoffrey. 2005. "¡Hip Hop, Revolución! Nationalizing Rap in Republic of cuba". Ethnomusicology 49, no. iii: 368–402.

- ^ Sandra Levinson An exclusive interview with Harry Belafonte on Republic of cuba. Cuba Now, 10/25/03.

- ^ "Reception Honoring Oliver R. Tambo, President, The African National Congress (South Africa)". African Activist Archive. Matrix. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ "Found for Policy Studies: Trustees". Ips-dc.org. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved Nov 5, 2013.

- ^ Baker, Brent (October x, 2002). "Belafonte Calls Powell Bush'southward "House Slave"". Media Inquiry Center. Retrieved December x, 2013.

- ^ "Belafonte won't back down from Powell slave reference". CNN. Oct xiv, 2002. Archived from the original on December 25, 2009. Retrieved May iv, 2010.

- ^ "Powell, Rice Accused of Toeing the Line". Fox News. October 22, 2002.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte on Bush, Republic of iraq, Hurricane Katrina and Having His Conversations with Martin Luther King Wiretapped by the FBI". Democracy At present!. Archived from the original on November 16, 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Venezuela plans to expand programme to provide cheap heating oil to U.s. poor". Taipei Times. October 29, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Belafonte calls Bush 'greatest terrorist' - World news - Americas | NBC News". NBC News. January 8, 2006. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "Chavez Repeats 'Devil' Comment at Harlem Event". Fox News. September 21, 2006.

- ^ "Article". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on February 18, 2007.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte Comments" (Printing release). AARP.org. Nov 1, 2013. Retrieved November five, 2013.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte on Bush, Iraq, Hurricane Katrina and Having His Conversations with Martin Luther King Wiretapped by the FBI". Commonwealth Now!. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ Williams, Brad (September 13, 2006). "Audience applauds Belafonte". The Daily Beacon. 35.953545;-83.925853: University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "POLITICS-US: Belafonte on Thinking Exterior the Ballot Box". Ipsnews.net. Archived from the original on February xx, 2012. Retrieved November four, 2013.

- ^ "Belafonte Blasts 'Gestapo' Security". Fox News. Jan 23, 2006.

- ^ Goodman, Amy (May 16, 2011). "Sing Your Song: Harry Belafonte on Fine art & Politics, Ceremonious Rights & His Critique of President Obama". Democracy Now! . Retrieved Dec 10, 2013.

- ^ "Barack Obama's father on colonial list of Kenyan students in US". The Guardian. April 17, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte on Obama: "He Plays the Game that He Plays Because He Sees No Threat from Evidencing Concerns for the Poor"". Commonwealth Now!. January 26, 2011.

- ^ Francis, Marquise (December 14, 2012). "Harry Belafonte: Obama should 'piece of work like a third world dictator'". The Grio. MSNBC. Retrieved June twenty, 2013.

- ^ "NAACP Image Awards | Harry Belafonte Speaks on Gun Control in Acceptance Spoken language | February 1, 2013". YouTube. February ii, 2013. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved Feb 19, 2013.

- ^ "NYC Pride Press Release" (PDF). Nycpride.org.

- ^ Bernie 2016 (Feb eleven, 2016), Harry Belafonte Endorses Bernie Sanders for President , retrieved February 11, 2016

- ^ Aneja, Arpita (January 21, 2017). "Gloria Steinem Harry Belafonte March on Washington VIDEO". Time . Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ "Harry Belafonte - The Sanders Institute". sandersinstitute.com.

- ^ "Ode aan Bonaire, een ongrijpbare liefde in de Caraïbische branding". ThePostOnline via Knipselkrant Curacao (in Dutch). Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Belnemproject". Amigoe via Delpher.nl (in Dutch). Apr 21, 1981. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Statuten Bel-Nem goedgekeurd". Amigoe di Curacao via Delpher.nl (in Dutch). June 29, 1966. Retrieved May iii, 2021.

- ^ "Bonaire, bevolkingscijfers per buurt". Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (in Dutch). 2017. Retrieved May three, 2021.

- ^ Cast (Harry Belafonte and the Belafonte Singers; Johnny Carson; Martha Raye). The Steve Allen Bear witness Season 4 Episode 9.

- ^ Grow, Kory (January eight, 2015). "Roger Waters, John Mellencamp Choose Interviewers for 'Speakeasy' Television Show". Rolling Stone . Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ Schuessler, Jennifer (March 14, 2020). "A Great 24-hour interval-O for Black Culture". The New York Times. No. Arts pp C1, C3.

Further reading [edit]

- Sharlet, Jeff (2013). "Vocalism and Hammer". Virginia Quarterly Review (Autumn 2013): 24–41. Retrieved Oct 4, 2013.

- Smith, Judith. Becoming Belafonte: Blackness Artist, Public Radical. University of Texas Printing, 2014. ISBN 0292729146, ISBN 9780292729148.

- Wise, James. Stars in Blue: Motion-picture show Actors in America's Sea Services. Annapolis, Medico: Naval Institute Printing, 1997. ISBN 1557509379. OCLC 36824724.

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Belafonte

0 Response to "Harry Belafonte = Mary and the Baby Hungry"

Enregistrer un commentaire